Joint statement from ARZA, ARC and the UPJ

Joint statement by the Union for Progressive Judaism (UPJ), the Australian Reform Zionist Association (ARZA) and the Assembly of Rabbis and Cantors of Australia, New Zealand and Asia (ARC)

The Australian Jewish Progressive Movement would like to express their support of the statements made by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the Zionist Federation of Australia with regard to the speech given by Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong to the Australian National University national security conference on Tuesday 9 April suggesting the recognition of a Palestinian state by Australia.

While the Australian Jewish Progressive Movement remains committed to a viable two-state solution to the present situation, we do not agree to the premature recognition of a Palestinian state, which has not yet been negotiated.

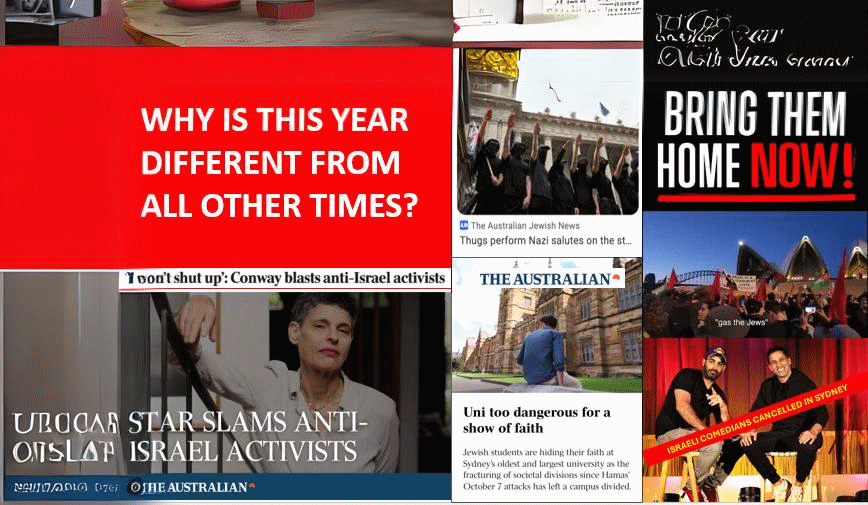

We also believe that any ceasefire without the release of the hostages and without an acknowledgement of the war crimes committed by Hamas is a one-sided agreement.

Danny Hochberg and Larry Lockshin

UPJ Co-Presidents

Ayal Marek

ARZA President

Rabbi Allison RH Conyer

ARC Chair